By Scott Ellwood, Bruce and Mary Crawford Assistant Librarian

The Grolier Club Library has rotating exhibits of books from our collections in four small cases in the reading room. The following text and examples come from the current exhibit, “Illustrating Bibliography,” installed on April 24, 2023. The Library is always open to Grolier Club members during our regular hours, and researchers may visit with an appointment by emailing our Librarian.

“The object of Bibliography is to bring a book or set of books, in their absence, as much as possible before the student.”

– Falconer Madan “On Method in Bibliography”

Bibliography took a “scientific” turn in the second half of the 19th century, in tandem with the rise of photographic reproduction processes. Though earlier bibliographies, catalogues, and other publications about books and printing included occasional illustrations for various purposes, mechanical reproduction opened new possibilities for a bibliography based on physical evidence. Photography only broke into bibliographical literature on a large scale beginning in the 1870s with the spread of photomechanical reproductions, but the medium’s influence can be felt from the late 1830s onward, pushing reproductions to higher levels of fidelity, even when facsimiles were still traced or drawn by hand.

Photography’s apparent mechanical perfection had an aesthetic and intellectual allure for material studies, from bibliography to art history. This exhibit explores a few examples of how bibliographies leveraged and responded to photography in their illustrations, all of them reaching for greater veracity, enticement, and authority than texts alone.

THE AESTHETIC draw of photography goes hand in hand with its mechanical exactness. Booksellers and auction houses would soon grasp that it could be a useful tool in sale catalogues, where the books must be both authentic and attractive. The Sotheby’s catalogues for Guglielmo Libri’s 1859 sales record the first instance of an auction catalogue capitalizing on photographic techniques, decades before they became a regular fixture.

The notorious book-thief and fabricator Guglielmo Libri’s 1859 sales at Sotheby’s are landmark catalogues for their extensive descriptions and illustrations. The 37 lithographed plates in this catalogue follow a tradition of reproducing manuscripts’ calligraphy and illuminations that began at least as early as the 18th century in sale catalogues. These renderings augment Libri’s text, but they lack a seductive appeal. (See Fig. 1 below)

Libri’s August 1859 sale catalogue may be the earliest auction catalogue issued with photographic illustrations, though they were distributed separately upon application. In “The Uses of Bookbinding Literature,” Bernard Breslauer noted the Libri catalogue’s primacy, but the copy he referenced that has those photographs is perhaps unique, and otherwise unrecorded.[1] We are left imagining their enticement for collectors in 1859. (See Fig. 2 below)

PHOTOGRAPHS can read like visual facts – or indisputable evidence in John Ruskin’s words – to support bibliographic arguments. But a perfectly accurate reproduction is not necessarily authentic or authoritative. Photographs can lend bibliographies a sense of precision that may turn out to be unearned.

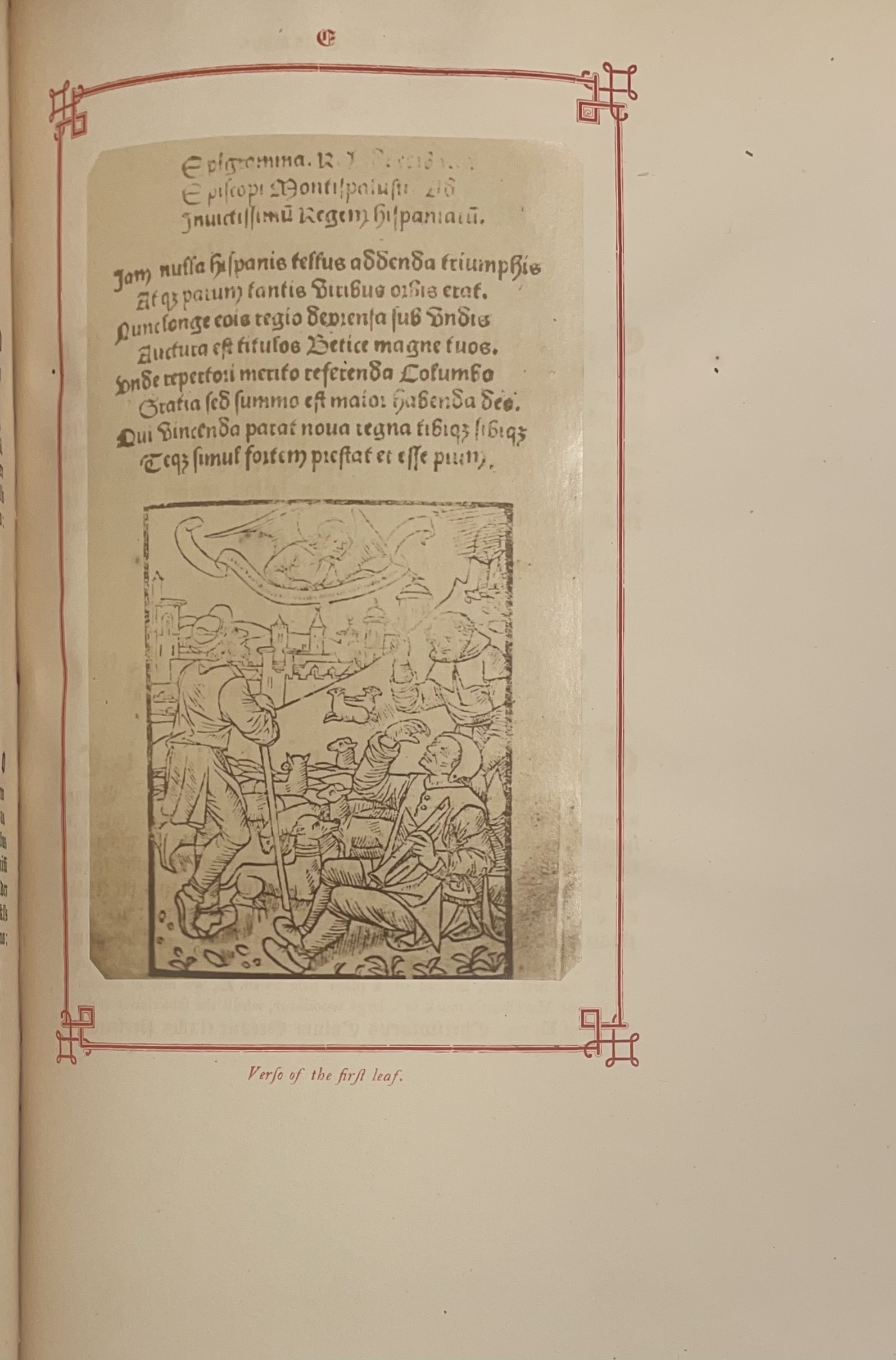

Photographs add scholarly weight to books (like certain formats, type, or paper), and bibliographers like Henry Harrisse recognized that. In his ‘humble’ Notes on Columbus, he writes: “[W]e do not attach an undue importance to this volume, in so far as its contents are concerned, nor do we wish to be held accountable for the sumptuous style in which a Dibdin-like friend of ours has chosen to have it printed, illustrated and embellished.” (See Figs. 3a-3b below)

The medium of photography can lend undue legitimacy to illustrations themselves, because it is sometimes impossible to tell a photograph of an original from a photograph of a facsimile, as with this heliotype of a pen facsimile from the “wonderful hand-work of [John] Harris.” Photographs strip away so much material evidence that they can counterintuitively hide a fabrication in plain sight, whether intentional or not. (See Figs. 4a-4b below)

ILLUSTRATIONS add authenticity to bibliographical works in subtle ways. They demonstrate the bibliographer’s familiarity with the physical material, and they project the primary evidence, albeit mediated, onto the page for the reader to examine. On another level, the implied cost of illustrations is a proxy assurance of the text’s value and can help verify the author’s own edition against counterfeiters.

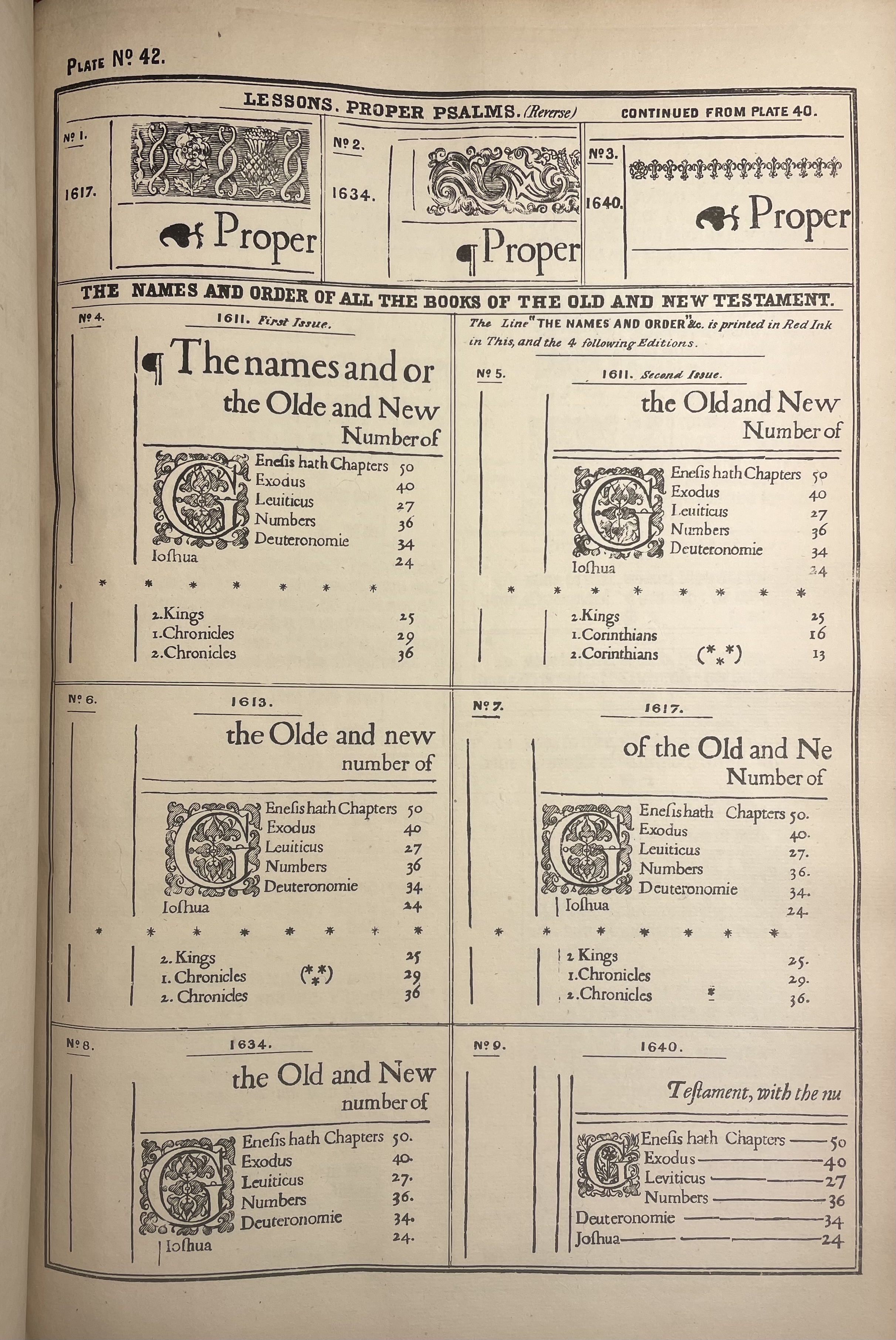

Brunet’s famous bibliographic handbook for booksellers and collectors ran through three ever-expanding editions from 1810 to 1820. Then the Société Belge de Librairie pirated it in 1838. Brunet responded with a lesson from printing history and scattered reproductions of printers’ devices throughout his own 4th edition. They served the very purpose for which printers’ devices were originally created: to mark the work’s authenticity and deter piracy. These illustrations predate commercially viable methods of photomechanical reproduction, so Brunet had to access the printers’ devices, create original facsimile illustrations, and translate them into electrotypes for printing. Here we have an original facsimile illustration; the publisher’s album of proofs with its electrotype; and the final image in the published work. (See Figs. 5a-5c below)

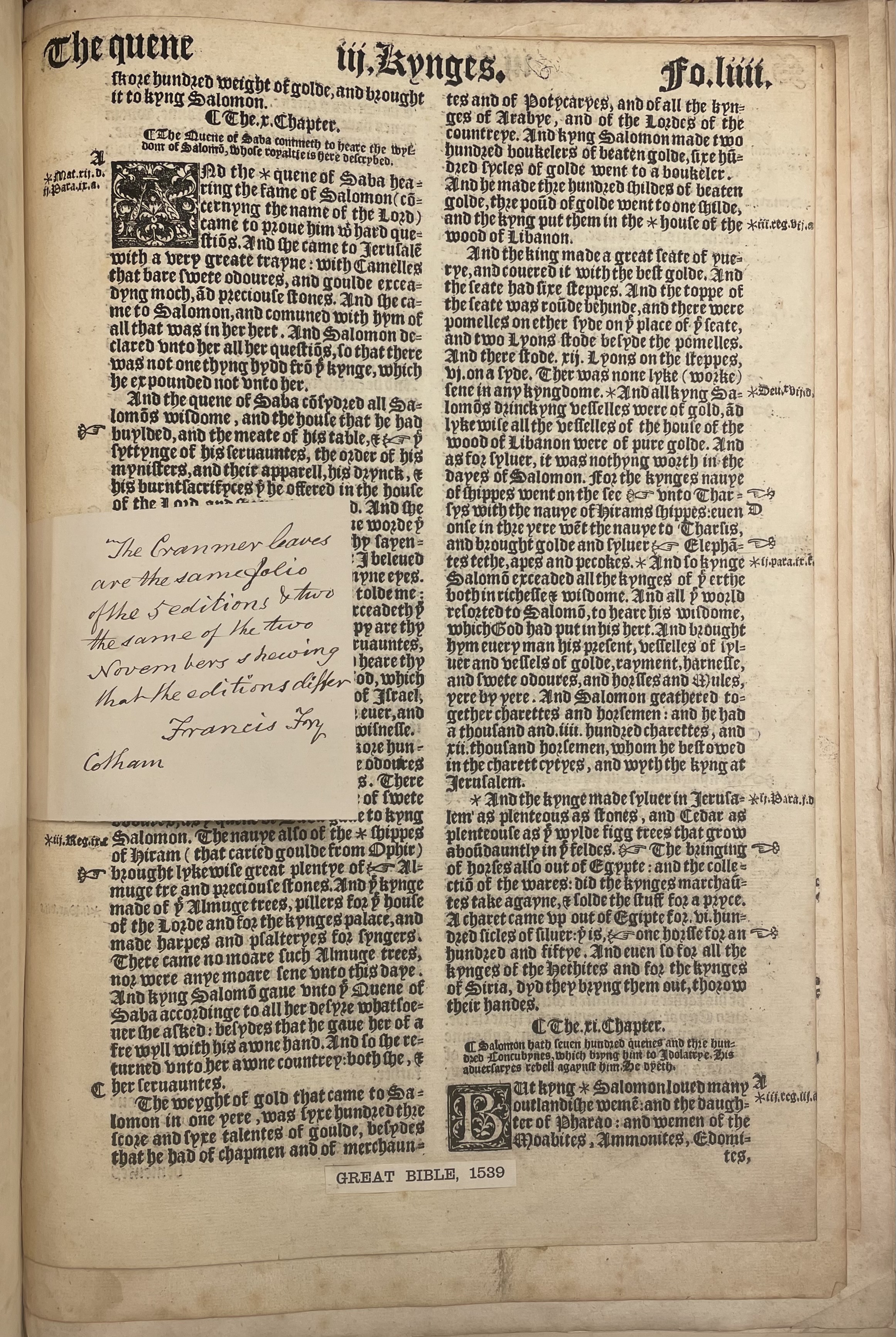

ILLUSTRATIONS in catalogues and bibliographies bring the listed books closer to the reader, approximating the feeling of examining the original material alongside the bibliographer, but reproductions only go so far. The most careful hand-drawn facsimile and the highest quality collotype are still simulacrums, but original leaves from the books being studied provide a material authenticity that cannot be reproduced.

Francis Fry’s study of early printed English Bibles attempts to provide identifying points for the edition of each individual leaf (14 editions total). He uses copious illustrations – meticulously traced by hand, down to the inky shoulders – to identify points of difference. Moreover, Fry included an original leaf from each edition described “for many of the particulars mentioned will thus meet the eye on the original leaves.” (See Figs. 6a-6b below)

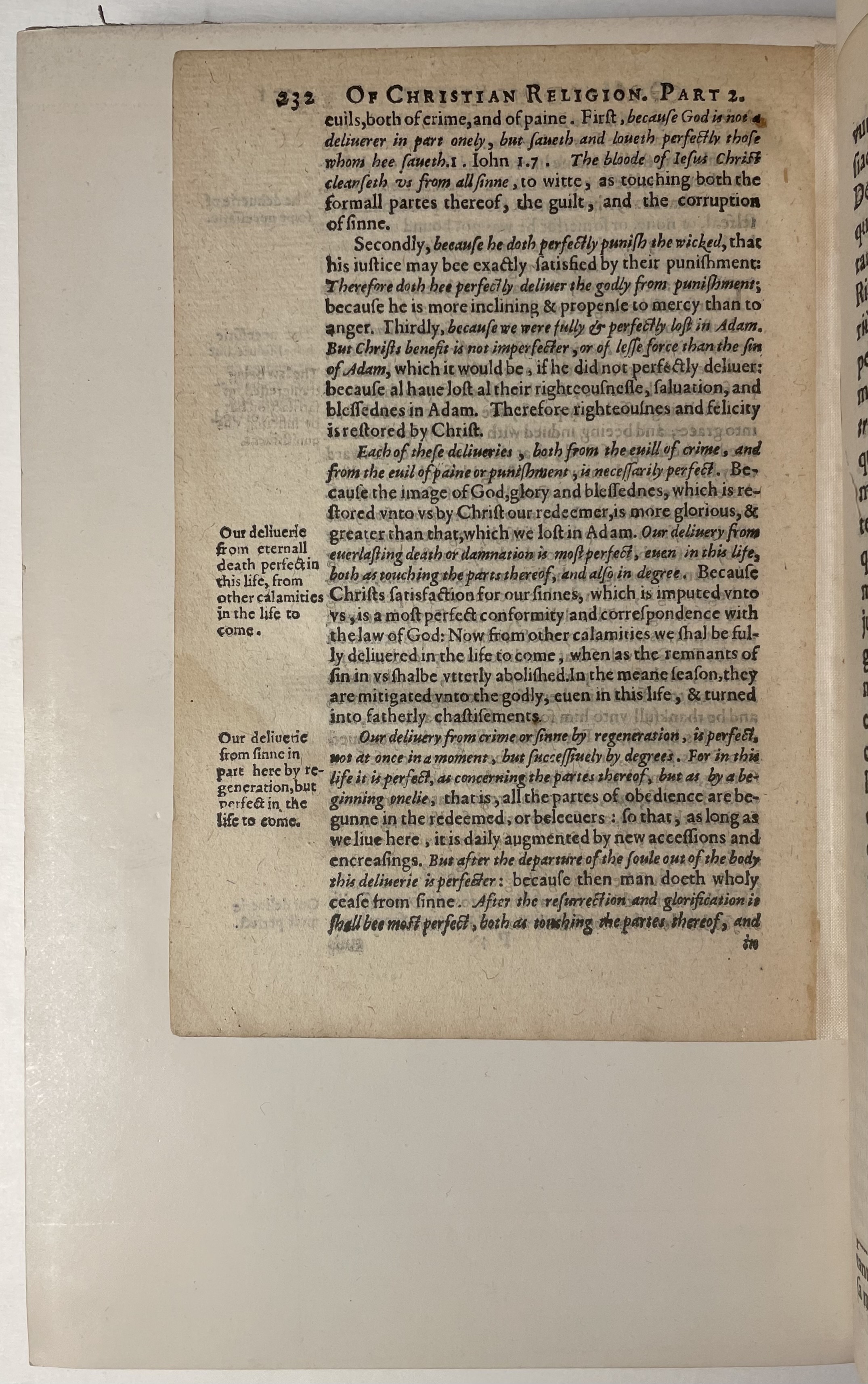

Falconer Madan’s ideal bibliography, outlined in “On Methods in Bibliography,” ought to include photographs when the bibliographer runs against “the inadequacy of language to describe.” He did as much in Oxford Books: A Bibliography, with 7 collotypes illustrating various Oxford presses’ types. However, he still felt that three original leaves were needed to give readers a taste of the historical texture of these Oxford books, even in their absence. (See Figs. 7a-7b below)

Illustrations in bibliographies and catalogues resist a simple relationship to the text as supporting evidence. In many ways, the reproduction technique and treatment of the illustrations insinuate how readers should use and rely on the work as a whole, pressing on key issues of authenticity and authority. Just as with the sciences or art history, reproduction technologies, especially photo-mechanical reproductions, play a decisive role in the historiography of bibliography. Focusing on illustrated bibliographies reframes the development of the discipline within the development of books’ commercial, cultural, and technological endeavors (in other words, within book history). Highlighting those bibliographies with illustrations perforates the boundaries of bibliographical canons to give us a fresh perspective on how the study of books evolved in certain directions. With the rise of digital images, research methods have corralled around reproductions and images as evidence and argument; a critical approach to illustrations in our field’s history will help us use them with more skill, intention, and comprehension for how they continue to influence our collecting, trade, pedagogy, and research of books.

Works Exhibited:

1. S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson. Extraordinary collection of splendid manuscripts, …, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri … London: Sotheby & Wilkinson, March 28, 1859.

Illustrated by lithographs, from facsimile illustrations.

2. S. Leigh Sotheby & John Wilkinson. Catalogue of the choicer portion of the magnificent library, formed by M. Guglielmo Libri … London: Sotheby & Wilkinson, August 1, 1859.

Illustrated by photographs (not present with this copy); distributed on request and to be returned.

3. Harrisse, Henry. Notes on Columbus. Cambridge, Massachusetts: [Samuel Latham Mitchill Barlow] ; Printed at the Riverside Press, 1865.

Illustrated by albumen photographs and line blocks (not displayed), possibly photomechanical.

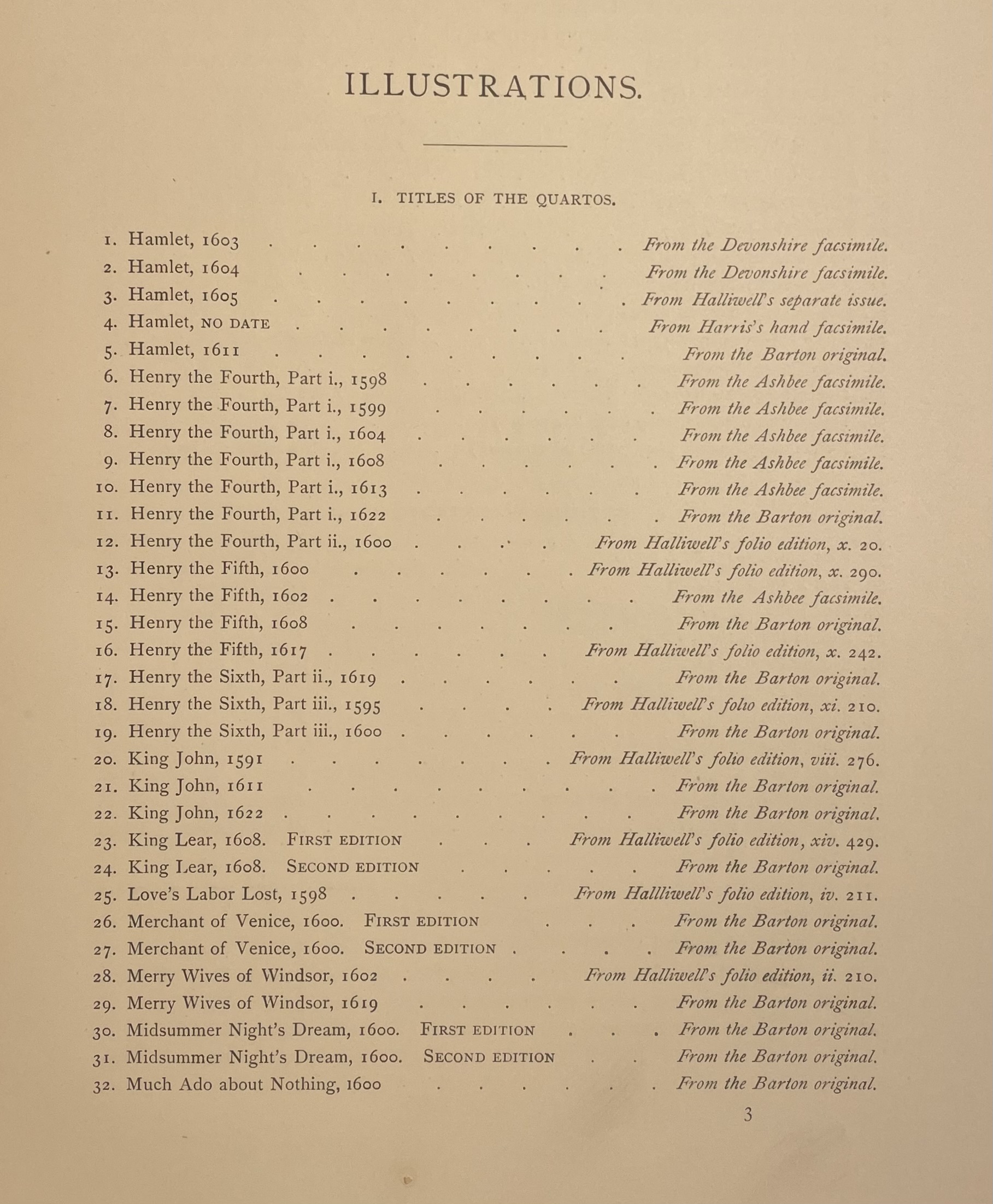

4. Winsor, Justin. A bibliography of the Original Quartos and Folios of Shakespeare. Boston: J.R. Osgood and Company, 1876.

Illustrated by heliotypes. Displayed is a heliotype of a pen facsimile by John Harris.

5a. Brunet, Jacque-Charles. Manuel du Libraire et de l’Amateur de Livres. 4th edition. Paris: Silvestre, 1842-1844.

From the Grolier Club’s Jacques-Charles Brunet Manuel du libraire Collection.

Illustrated by electrotypes, from facsimile illustrations.

b. Facsimile illustration of Gilles de Gourmont’s printer’s device. [Paris: ca. 1838-1842].

From the Grolier Club’s Jacques-Charles Brunet Manuel du libraire Collection.

Original illustration for electrotype, in ink and graphite; facsimile of printer’s device.

c. Proof album of 308 reproductions of printers’ devices for the 4th edition of Brunet’s Manuel du Libraire et de l’Amateur des Livres. [Paris: ca. 1838-1842].

From the Grolier Club’s Jacques-Charles Brunet Manuel du libraire Collection.

Electrotype and cliché proofs, from facsimile illustrations.

6. Fry, Francis. A Description of the Great Bible, 1539 and the Six Editions of Cranmer’s Bible, 1540 and 1541. London; Bristol: Willis and Sotheran; Lasbury, 1865.

Illustrated by original leaves (not displayed) and lithograph facsimiles, traced by the author from his own copies.

7. Falconer Madan. Oxford Books: A Bibliography. The early Oxford press, 1468-1640 [vol. 1]. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1895-1931.

Illustrated by original leaves and collotypes (not displayed).

Further Reading

Bibliography

Breslauer, Bernard and Roland Folter. Bibliography: Its History and

Development. New York: The Grolier Club, 1984.

James, Kathryn and Aaron T. Pratt. “Collated & Perfect.” In Bibliomania;

or Bookmadness: A Bibliographical Romance. New Haven: Office of the Yale University Printer, 2019.

Madan, Falconer. “On Method in Bibliography.” Transactions of the Bibliographical

Society 1, parts 1-2 (1893): 91-106.

Needham, Paul. The Bradshaw Method: Henry Bradshaw’s Contribution to

Bibliography. [Chapel Hill]: Hanes Foundation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1988.

Tanselle, G. Thomas. “Bibliography and Science (1974)” and “The Evolving

Role of Bibliography, 1884-1984 (1984).” In Essays in Bibliographical History. Charlottesville: The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 2013.

Printmaking and Photomechanical Reproduction

Bridson, Gavin D.R. and Geoffrey Wakeman. Printmaking & Picture

Printing: A Bibliographical Guide to Artistic & Industrial Techniques in Britain, 1750-1900. Oxford: Plough Press, 1984.

Hanson, David A. and Sidney Tillim. Photographs in Ink. Teaneck, New

Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1996.

Stannard, William. The Art Exemplar. [London: Stannard and Rae, 1859?].

http://dcmny.org/islandora/object/gc%3Atheartexemplar.

Photographs in Art Historiography

Fawcett, Trevor. “Visual Facts and the Nineteenth-Century Art Lecture.”

Art History 6, no. 4 (1983): 442–460.

Nelson, Robert S. “The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art ‘History’ in the

Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Critical Inquiry 26, no. 3 (Spring 2000): 414-434.

[1] I am indebted to Michael Laird for the reference to Breslauer’s lecture, published by the Book Arts Press.