The Grolier Club Library has rotating exhibits of books from our collections in a Breakfront on the 5th floor as well as four small cases in the reading room. The following text and examples come from the current Breakfront exhibit, “Paper-Making as Art, Totem, and Technology,” installed on March 8, 2023. The Library is always open to Grolier Club members during our regular hours, and researchers may visit with an appointment by emailing our Librarian.

This exhibition looks at examples of works about papermaking in the Grolier Club’s collection that demonstrate paper’s significance for the modern, Western, and colonizing world in connection to papers constructed as traditional, natural, or primitive. One of the goals with these selections is to show that the romanticism projected onto non-Western paper cultures reflects attitudes toward paper within industrial and post-industrial contexts. The title, “Paper-Making as Art, Totem, and Technology,” refers to the levels of often unstated meanings wrapped into every item selected for display, particularly for the modern, Western actors who produced or collected them.

The following blog post has a list of the items on display with notes on the exhibit’s theme. The first item was the inspiration for this display, and it has an extended text.

1. Lenz, Hans. El papel indígena mexicano: historia y supervivencia. Mexico City: Rafael Loera y Chávez, Editorial Cultura, 1948.

In 1948, an anthropologist who collected and specialized in the study of indigenous Mexican papers, Hans Lenz, published this stunning folio volume. As an appendix, he included several collected paper specimens and muñecos (paper dolls representing specific spirits from the land), captioned with the name of the indigenous people who made it (e.g. Otomí, Nahua, etc.), the plant fibers used, and general designations of their significance. Two muñecos in particular, cut to the shape of anthropomorphic figures, are labelled as generic “good” and “evil spirits.” Cut from dark, fibrous paper, the so-called evil spirit’s delicate claws, teeth, and eyes stand in organic contrast to the machined, smooth, bleached paper it is mounted upon. The white leaf holds it in a sterilized space, like the white cube of a museum with a tidy label:

MUESTRA 3.—PAPEL DEL XALAMATL GRANDE. FIGURITA RECORTADA POR LOS INDÍGENAS OTOMÍES DE SAN PABLITO, ESTADO DE PUEBLA. REPRESENTA A UN ESPÍRITU MALO. [1]

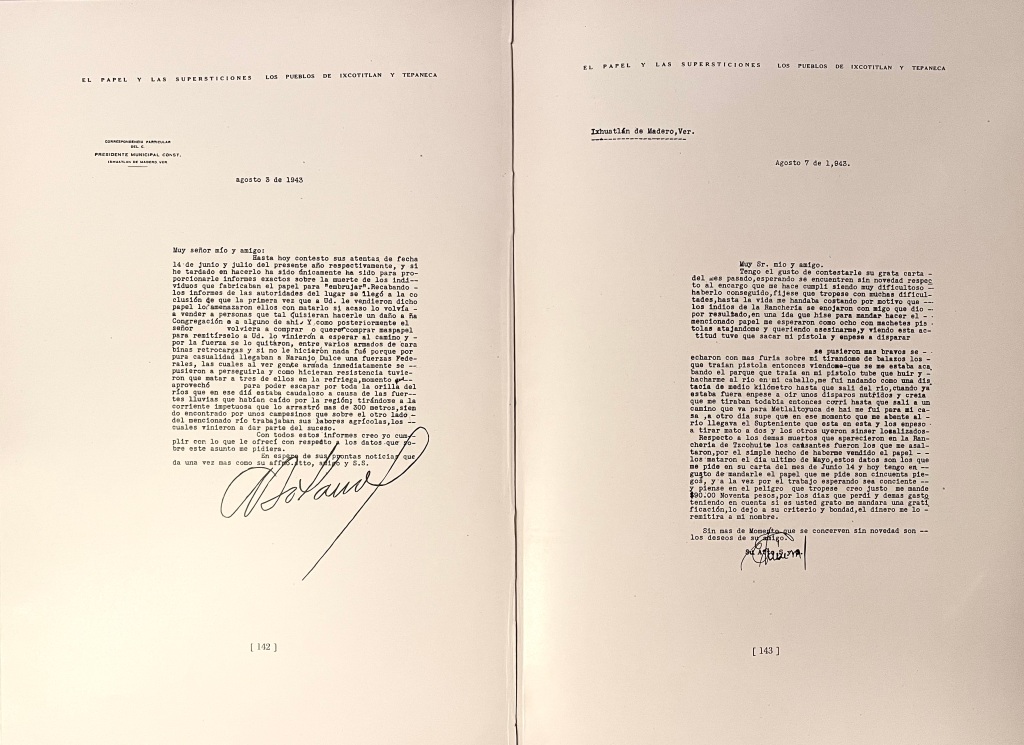

Philip P. Arnold wrote about Lenz’s book in his article, “Paper Ties to Land: Indigenous and Colonial Material Orientations to Mexico.”[2] He highlights an episode about how Lenz acquired a particular set of papers from a papermaking couple in the Nahua community of Ixhualtlan de Madero. They were curanderos, able to heal and ensure good harvests with their paper because they could, as Arnold says, “make the particular papers needed to propriate those deities [who resided in the landscape].”[3] Their community did not want them to sell these papers that had significant power, but Lenz convinced them to make and sell him the papers in secret. Ultimately, his local representative purchased the papers only to face an armed band from the community, who had already killed the couple for their transgression. Lenz’s representative escaped unharmed, but federal Mexican forces engaged with the band, killing two or three of them.

In El Papel Indígena Mexicano, Lenz reproduces his correspondence with the federal police administration. He described the event, according to Arnold, “without offering any explanation as to its significance.” Arnold goes on to write:

“What was at stake in this conflict between native Nahua people, Lenz, and the federal forces? … What alternative meanings of paper justified the deaths of these Nahua people? Clearly paper in the native context is more intrinsically valuable than in the modern world. Although Lenz is interested in these papers he seems incapable of assessing their significance. He values these papers only with reference to a monetary system—not with reference to an indigenous understanding. It is my contention that this event starkly illustrates the distance between indigenous and colonial (i.e. modern) understandings of paper and its performative place in the occupation of the Americas.”[4]

While Lenz did not recognize the full meaning of these papers, and while there is a significant difference between their indigenous and colonial meanings, these meanings may not be as distant as Arnold argues. Lenz affects a divide between his “modern” understanding of the paper and the indigenous by creating contrast in his caption text. Lenz describes the muñeco on the one hand by its botanical matter and on the other hand as a decontextualized “evil spirit,” setting the precision of modern scientific knowledge against a portrayal of imprecise, fanciful indigenous knowledge. His performative objectivity hides a reality that paper holds as much symbolic significance for colonizers as the colonized.

We can compare Lenz’s treatment of these muñecos with the Amate Manuscripts of Alfonso García Tellez. He was a self-described brujo (witch), or curandero (curer), trained by his father. They lived in San Pablito, the same place Lenz’s collected muñecos come from. Note especially the similarity to the muñecos of García Tellez’s Tratamiento de una Ofrenda para Pedir la Lluvia en San Pablito Pahuatlán Pue[bla], which gives specific explanations of the represented deities’ connections to particular plants and aspects of the land.[5] García Tellez’s manuscripts perhaps resonate as him pushing against intrusions and misrepresentations of his culture by appropriating the colonizers’ book-form, anthropology, and souvenir traditions, bringing to mind the intentions and strategies of the Techialoyan Codices from 17th and 18th century Mexico.[6] The contrast with Lenz’s “evil spirit” label demonstrates the biases and potential falsehoods embedded in Lenz’s portrayal of indigenous paper-knowledge.

Arnold writes of Nahua indigenous papers:

“Not only were these papers important ritual items infused with an ability to interact with deities in the landscape, but they also symbolized a direct connection between this Nahua village and the land. So close was the connection between native paper and land that selling these native papers to Lenz was like giving up the land.”[7]

When Arnold rhetorically asks, “What alternative meanings of paper justified the deaths of these Nahua people,” he focuses on why the Nahua band killed and died trying to protect the paper, excluding the related question of why Lenz, his representative, and the federal forces were willing to kill to take it. The paper had great symbolic significance for Lenz and his modern readership; if not tantamount to taking Nahua land, taking the paper represented a level of intellectual and bureaucratic control over the land and people who made it. In this way, the indigenous and colonial “understandings of the paper and its performative place in the occupation of the Americas” are not so distant. Still, Arnold is correct that Lenz is “incapable of assessing [the paper’s] significance,” not just for the Nahua but also for himself and his own community. Lenz does not seem to recognize the symbolic power of paper in the modern world.

2. Studley, Vance. “Iris.” Specimens of handmade botanical papers. Los Angeles: Press of the Pegacycle Lady, 1979.

In Studley’s suite of six botanical etchings, the image of the mulberry plant is paired with a leaf of mulberry paper, the thistle with thistle paper, and so on. He represents each plant with its image and the paper made from its fibers, highlighting the creative connection to nature that handmade paper can conjure. Studley’s work demonstrates care for these plants and the papers made from their fibers, with an artistic significance not entirely dissimilar from the spiritual power the Nahua and Otomí recognize in the papers they make. I paired this suite of prints with Lenz’s El Papel Indígena Mexicano as a starting point for this display, to highlight that Lenz has misleadingly downplayed the significance of paper for his own Western culture.

3. Gotō, Seikichirō. Japanese hand-made paper: Japanese paper and paper-making. Volume 2, Western Japan. [Japan]: Bijutsushuppan-sha, 1960.

Gotō gives an immense, two-volume survey of Japanese papermaking from a Japanese perspective, translated for an English-speaking audience. His travelogue style work draws connections between the localities, traditions, papers, and printing arts of Japan, including samples of the paper described. Often, the paper samples carry prints to demonstrate their suitability to an aspect of printmaking. The treatment of the prints as paper specimens shows a heightened awareness for the way paper affects the texts and images it supports in meaningfully aesthetic ways.

4. Great Britain. Parliament. Reports on the manufacture of paper in Japan: presented to both houses of Parliament by command of Her Majesty, 1871. London: Printed by Harrison and Sons, 1871.

In 1869, the British Ambassador to Japan, Harry S. Parkes, and his three consuls were instructed by the Foreign Secretary to prepare a report on the various uses of paper in Japan, including their types and manufacture. The Parkes Report included paper specimens sent to the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria & Albert, as a collection for technical study, and the report made its way to the Trade Commission to inform British paper manufacturers of the modes and methods of Japanese paper. Interestingly, the illustrations accompanying the report were copied to lithographs from watercolors done by a Japanese artist, likely copying the woodcuts of Seichuan Niwa Tokei for Jihei Kunisaki’s Kamisuki Chohoki (“Handy Guide to Papermaking,” Osaka, 1798). The loosely sketched illustrations contrast with the rigidly ordered text that attempts to structure them within a new context, for British government and trade to consume. The production and components of the Parkes Report run parallel to Lenz’s El Papel Indígena Mexicano in many respects, leaving the question, what were Westerners hoping to find in other papermaking cultures?

5. Hunter, Dard. A papermaking pilgrimage to Japan, Korea and China. New York: Pynson Printers, 1936.

Dard Hunter was an interesting figure in the history of papermaking because he revived hand papermaking in the United States after it had died out commercially. In addition to studying the history of papermaking in Europe and the United States, he studied other paper cultures, from Mexico to India to Japan, Korea, and China. The spiritual reverence that resonates in his word “pilgrimage” seems to reflect the fulfilment he found in papermaking, but this does not mean he blindly romanticized papermaking in Japan. Here, Dard Hunter photographs a Japanese paper mill in a production line very similar to Lalande’s 18th-century image shown below.

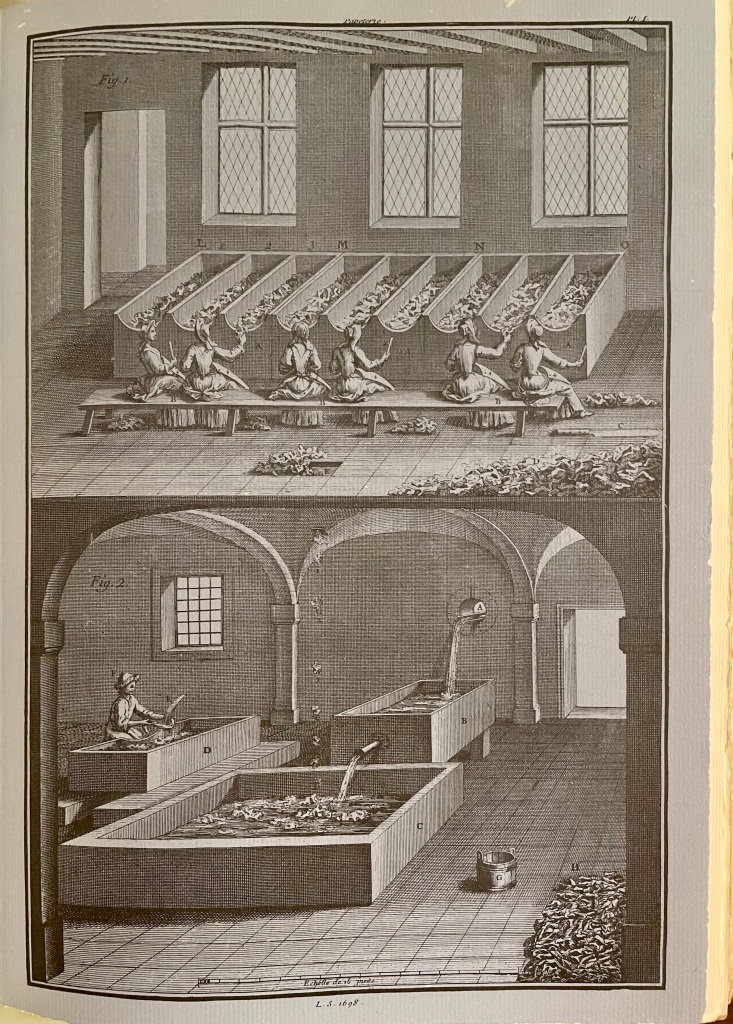

6. Lalande, Joseph Jérôme Le Français de, 1732-1807. The art of papermaking. Kilmurry, Sixmilebridge, Co. Clare, Ireland: Ashling Press, 1976.

This fine press edition of Lalande’s work reproduces the original edition’s Encyclopédie-style etchings of assembly-line paper production at the dawn of the industrial revolution. The iconography of industrialized papermaking distinguishes the process from romanticized notions of craft papermaking that were often projected onto non-industrial paper cultures in the 19th and 20th centuries. Ironically, this is a fine press edition that approaches book-making with an artistic sensitivity, and it uses a blue paper with laid lines and deckled edges for all the illustrations to signal its respect for the craft.

7. Wasp’s Nest, ca. 1921. Gift of George F. Kunz, 1921. Gift letter from George F. Kunz to Librarian, Ruth Shephard Granniss, 1921.

8. Lummis, Charles Fletcher. Birchbark poems. Boston: J.S. Conant, 1882.

9. Champion Coated Paper Company. Paper making. [New York]: Champion Coated Paper Company, ca. 1922.

I grouped these three objects to demonstrate the slippery reality of paper as an environmental, cultural, and technological product that can carry a range of symbolic values. The first item is a flattened wasp’s nest given to the Grolier Club by a member, George F. Kunz. Our librarian kept the gift letter explaining that wasps are the “first paper makers” since they build their nests from macerated wood-pulp.

Charles Fletcher Lummis’s Birchbark Poems is printed on actual birch bark with some unprinted leaves included loose in each copy. Lummis’s material gimmick emphasizes the romanticism of his poetry. Birch bark is also a recognized material from North American indigenous craftworks, and Lummis was likely also fabricating a “primitive” aura that would have heightened the naturalism for his readers.

The Champion Coated Paper Company’s promotional set of papermaking ingredients mirrors the preciousness of the Birchbark Poems’ materiality. This set of boxes and glass vials highlights paper’s symbolism as product of science and industry.

All three objects foreground paper’s raw materials. Despite the contrast between the industrial tone of Champion Coated Paper Company’s chemistry set and the natural resonances of the wasp’s nest and Birchbark Poems, their shared elevation of paper’s materiality creates a harmony between them, which suggests common chords overlapping behind paper’s range of symbolic values.

10. Worthy Paper Company. Georgian Papers. Mittineague, MA: Worthy Paper Company, [ca. 1930?]

11. Louis DeJonge & Co. Samples. New York, Louis DeJonge & Co., [ca. 1930?]

12. Eastern Atlantic Manifest Certificate. Atlantic Pastel Offset and Color. [ca. 1960?]

13. Eastern Atlantic Manifest Certificate. Manifest Bond Mimeo and Duplicator. [ca. 1960?]

14. Thomas N. Fairbanks Company. Marais Mould-made in France with Four Deckle Edges and Felt Finished. New York: United States Envelope Company, [ca. 1940?]

These paper specimens of machined papers, from fine stationary to copy-shop stock for mimeo and off-set work, show the great variety of colors, weights, textures, and uses of commercial papers. They’re shown as a testament to the continued importance of paper as an art, technology, and nearly totemic material for the modern world, even if it is so ubiquitous as to be scarcely noticed.

By Scott Ellwood, Bruce and Mary Crawford Assistant Librarian

[1] Lenz, 250.

[2] Philip P. Arnold, “Paper Ties to Land: Indigenous and Colonial Material Orientations to Mexico,” History of Religions, special issue, Mesoamerican Religions, 35:1 (August 1995): 27-60.

[3] Arnold 27.

[4] Ibid. 29.

[5] Produced in [Mexico]: Alfonso García Tellez, [1975], Watson Library call number F1221.O86 G37 1975. García Tellez produced five known manuscript works in multiple but unique copies; copies for three of his works are held by the Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum, New York, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/in-circulation/2019/power-paper.

[6] See for example, Dana Leibsohn and Barbara E. Mundy, Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820, https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1685.

[7] Arnold 29.